Families are complex systems where every member’s behavior can influence the whole. Yet, trying to understand patterns, roles, and intergenerational dynamics can feel overwhelming, especially without a clear visual tool. Family systems theory offers a framework to make sense of these relationships, and when combined with genograms, it becomes easier to map patterns, roles, and emotional connections across generations.

What Is Family Systems Theory?

Family systems theory is a psychological framework that views the family as an interconnected system, where each member’s behavior affects the whole. Understanding family systems model helps therapists, counselors, and researchers examine patterns, relationships, and roles within a family to better address emotional, behavioral, and relational challenges. This theory is widely applied in therapy, psychology, and family studies because it highlights how individual issues often reflect broader family dynamics rather than isolated problems.

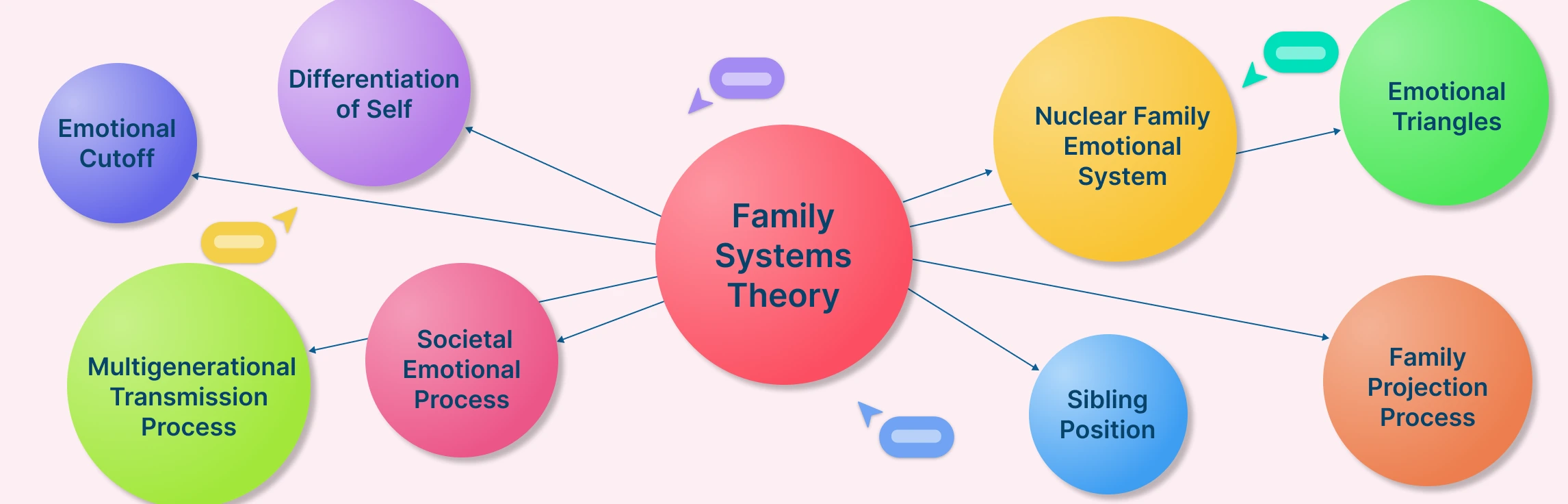

Bowen Family Systems Theory Explained

Developed by Murray Bowen, Bowen family systems theory emphasizes the importance of intergenerational relationships and patterns in shaping individual behavior. Bowen’s approach identifies recurring dynamics within families that influence emotional functioning, decision-making, and interpersonal relationships. His framework consists of eight key concepts, which are essential for understanding family behavior.

Core Concepts of Family Systems Theory

Understanding the family systems framework concept is key to analyzing patterns, roles, and relationships within families. Murray Bowen’s framework identifies eight concepts that explain how family members influence each other across generations. Here’s a breakdown of each, with examples to illustrate their application:

1. Differentiation of Self

This concept refers to a person’s ability to maintain their individuality while staying emotionally connected to their family.

Example: A teenager can make independent career choices without feeling guilty for disappointing their parents.

2. Emotional Triangles

Triangles occur when two family members in conflict involve a third to reduce tension, which can stabilize or complicate relationships.

Example: A child may act as a mediator between feuding parents.

3. Nuclear Family Emotional System

This concept examines recurring patterns of emotional functioning within the immediate family.

Example: Marital conflict may trigger anxiety or behavior changes in children.

4. Family Projection Process

Parents can transmit their unresolved anxieties or emotional problems to their children.

Example: A parent’s fear of failure may lead them to micromanage a child’s schoolwork.

5. Multigenerational Transmission Process

Behavioral and emotional patterns often repeat across generations, shaping family dynamics over time.

Example: Conflict avoidance observed in grandparents may continue in parents and grandchildren.

6. Sibling Position

Birth order impacts personality, roles, and responsibilities within the family system.

Example: The oldest child may naturally take on leadership duties, while the youngest may be more carefree or dependent.

7. Emotional Cutoff

Family members may manage unresolved conflicts by emotionally or physically distancing themselves from relatives.

Example: An adult avoids communicating with a critical parent to reduce stress.

8. Societal Emotional Process

Family dynamics are influenced by broader societal factors, including cultural norms, social pressures, and economic conditions.

Example: Job insecurity or cultural expectations can heighten family anxiety and affect decision-making.

Roles in Family Systems Theory

Understanding family systems theory roles helps explain how each member contributes to the family’s overall dynamics. In many families, individuals unconsciously adopt specific roles that influence interactions, responsibilities, and emotional patterns. Recognizing these roles can provide insight into behavior and improve communication within the family.

Caretaker

The caretaker is often responsible for managing the emotional or practical needs of other family members. They may act as a mediator in conflicts, provide support during crises, or ensure the household runs smoothly.

Significance: While the caretaker role can maintain family stability and foster trust, individuals in this role often neglect their own needs, leading to stress, burnout, or difficulty asserting boundaries.

Scapegoat

The scapegoat is frequently blamed for the family’s problems, whether justified or not. This role diverts attention from deeper issues within the family system.

Significance: Being the scapegoat can lead to low self-esteem, behavioral issues, or acting out. However, it also brings awareness to unresolved tensions and patterns that need addressing.

Hero

The hero strives for success or excellence to gain recognition or bring pride to the family. Often high-achieving and responsible, they may take on additional responsibilities to meet family expectations.

Significance: While the hero role can motivate achievement and maintain family morale, it may create pressure to overperform and conceal personal struggles or emotions.

Lost Child

The lost child tends to withdraw, avoid conflict, and minimize attention to maintain peace within the family. They may be quiet, independent, or unnoticed.

Significance: This role reduces family tension but can lead to isolation, low self-confidence, or difficulty forming close relationships outside the family.

Mascot / Family Clown

The mascot uses humor or playful behavior to lighten emotional tension or distract from family problems. They often provide comic relief during stressful situations.

Significance: While the mascot role can help diffuse conflict and ease anxiety, it may prevent them from addressing their own emotional needs and can mask deeper feelings of insecurity or fear.

Recognizing these family systems theory roles not only clarifies individual behavior but also helps therapists, counselors, and families develop healthier communication patterns and relationships.

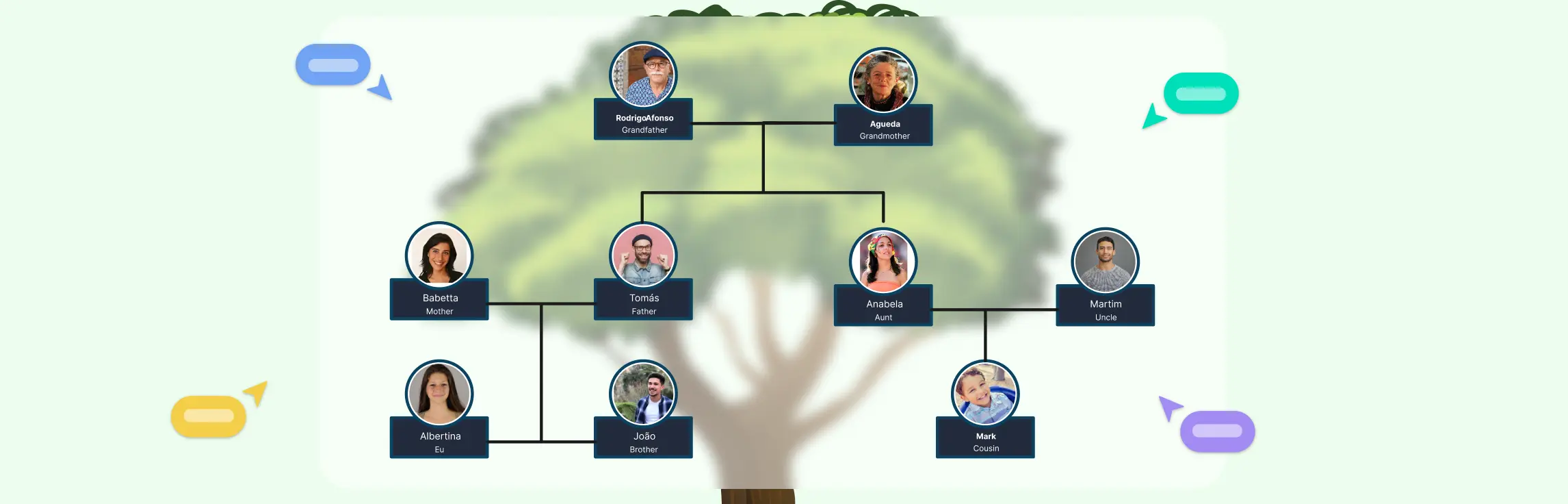

How to Visualize Family Systems Using Genograms and Family Trees

Visualizing family relationships is one of the most effective ways to apply family systems theory in practice. Tools like genograms and family trees help illustrate how individuals are connected, how emotional patterns develop, and how roles evolve over generations. These visuals not only make complex family dynamics easier to understand but also serve as essential tools in therapy, counseling, and social work.

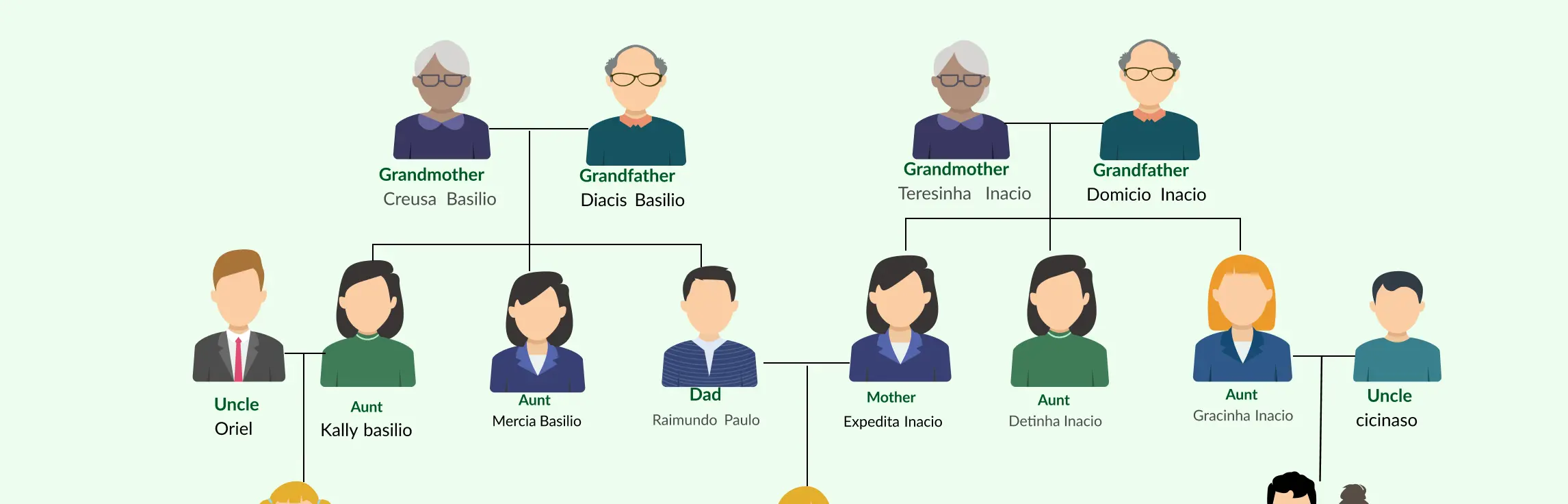

Genogram Templates to Illustrate Family Systems Theory

Genograms go beyond basic family trees by mapping emotional bonds, behavioral patterns, and psychological dynamics. Using an online genogram software, therapists, counselors, and researchers can better visualize interconnections within families and identify areas for growth or intervention.

1. Basic Genogram

The Basic Genogram provides a simple structure for mapping family members, their relationships, and key life events across generations. Use this template to map your family system and understand relationships better.

2. Emotional Relationship Genogram

This template highlights emotional bonds between family members, including close, distant, or conflicted relationships. It is ideal for identifying family patterns, roles, and tension points. Use this template to uncover how emotional dynamics shape family behavior.

3. Denominational Transition Genogram

The Denominational Transition Genogram tracks changes in religious or cultural affiliations across generations. It is particularly useful for understanding societal and spiritual influences on family systems. Use this template to explore how beliefs and transitions impact family patterns and roles.

4. 3 Generations Genogram

This template maps three generations of a family, showing intergenerational transmission of behavior, roles, and emotional patterns. It is an essential tool for applying Bowen’s concepts, such as multigenerational transmission and family projection. Use this template to visualize generational patterns and understand recurring family dynamics.

These genogram templates not only provide a visual representation of family systems theory but also make complex family dynamics easier to interpret and communicate. Whether you’re a therapist, social worker, or someone exploring your own family patterns, these templates offer a practical way to analyze relationships, roles, and emotional processes across generations.

Family Tree Templates for Mapping Generational Structure

Meanwhile, a family tree maker focuses on visualizing lineage, ancestry, and structural connections, making them an excellent starting point for anyone exploring their family history or tracing generational links.

Family trees are one of the simplest yet most insightful tools for understanding generational patterns within a family system. Unlike genograms, which include emotional and psychological dynamics, family trees focus on structural relationships — showing how family members are connected across generations. They help you trace lineage, identify recurring roles, and visualize the broader context in which family dynamics evolve.

You can use these family tree templates to map your family’s generational structure, uncover heritage patterns, and complement your genogram analysis. Whether you’re studying family systems theory in psychology, genealogy, or therapy, these templates make it easier to visualize how each member fits into the larger family network.

Family systems theory provides a powerful framework for understanding the roles, patterns, and emotional dynamics within families. By combining theory with visualization, you can map relationships, explore intergenerational patterns, and gain deeper insights into family functioning. Use these templates to start mapping your family system today and better understand how relationships shape behavior and emotions.

Resources:

Haefner, Judy. “An Application of Bowen Family Systems Theory.” Issues in Mental Health Nursing, vol. 35, no. 11, 29 Oct. 2014, pp. 835–841, https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.921257.

Rothbaum, Fred, et al. “Family Systems Theory, Attachment Theory, and Culture.” Family Process, vol. 41, no. 3, Sept. 2002, pp. 328–350, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41305.x.